A New Player Has Entered the Game: How Offshore Wind May be Entering Its Next Phase

Published August 2021

After a very interesting deal was concluded last month for Hollandse Kust Zuid by chemicals giant BASF, here are some thoughts by Everoze Partner Graeme Wilson on what this transaction might mean for the offshore wind industry and developers in particular.

Last month chemicals manufacturer BASF bought a 49.5% stake of the Hollandse Kust Zuid Wind Farm (HKZ) from developer Vattenfall. BASF not only took a stake in the project but also secured its share of power. This, according to their press release, is part of their strategy to secure significant volumes of electricity from renewable sources, in order to implement innovative, low-emission technologies.

This is not the first time an End User has bought a stake in an offshore wind farm to secure power. One other example is Kirkbi, who are 75% owners in Lego, who bought a stake Borkum Riffgrund 1 in 2012 and then in 2016 bought a stake in the Burbo Bank Extension. These acquisitions were intended to help Lego meet its goal of generating enough renewable energy to meet 100% of its energy needs in 2020.

What is different about this deal is that it comes at a time when the power and influence in the industry is shifting significantly and unpredictably. It means that if more players – End Users such as BASF and Lego – soon enter the game, it could signal the start of a new phase in the offshore wind industry.

The New Player

Those in the heavy industry sector, like BASF, tend to generate their electricity on-site, using CHP plants. This means that these End Users are effectively operating off-grid, and in many cases using gas, oil or solid fuel to power their generators. For heavy industry to decarbonise, much like BASF, they need to change the way they source their power.

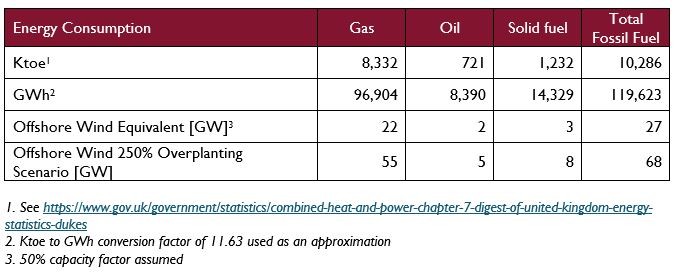

To give an idea of the scale of demand of heavy industry, BEIS publishes energy consumption figures annually as part of the Digest of UK Energy Statistics (DUKES). In 2019, of the energy consumed by heavy industry, 45% came directly from gas, oil or solid fuel.

Very high-level calculations below show that for heavy industry in the UK to source their power from renewables, may require 27 GW – 68 GW of offshore wind generation, depending on the over-planting needed.

As stated, these calculations are very high-level, but they do illustrate the magnitude of the challenge for the UK alone. Across Europe, many large companies with huge energy demands will soon need to find alternative ways of fuelling their plants.

Crucially in the case of HKZ, a subsidy-free project, BASF did not just secure an asset but also provided a route to market by taking the power too.

This goes some way to explain why the offshore wind industry may be shifting. Heavy industry energy End Users need green power and there’s already high demand from elsewhere in the market, both domestically and also through corporate PPAs. This is why, for now at least, the premiums of buying into projects through M&A processes are worth it if you can secure green power.

The Incumbent Developers

On the surface, the HKZ deal does look like a good result for incumbent developers everywhere. A new entrant coming along to increase competition and drive premiums up, in much the same way as O&G majors did last year – this must be good surely?

Perhaps in the short term. But what is clear is that much like the O&G majors last year, the M&A route is likely just a temporary strategy for the End Users. A necessary evil in order to secure the green power and experience they need to get the ball rolling on their long-term strategy.

For the End Users, it’s important to remember that their business expertise is focused on manufacturing, building, and large-scale, multinational production. Ideally, they want to continue to invest in their core business and not tie up billions of Euros in offshore wind projects for 35 years, with exposure to the risks that come with construction and operations.

So what might the End User do to take more control of the situation?

As the market shifts to subsidy-free offshore wind and subsidies that are available drop below long-term power price forecasts, big energy End Users that can offer long-term and large capacity PPAs to the projects could become a more significant factor in determining project economics. If End Users are able to pay the premiums required to secure equity in projects, perhaps this premium could instead be diverted into the PPA price.

As well as providing a lucrative route to market for electricity, End Users in the Chemical, Process and Food & Drink industries have in-house expertise which could smoothen the process of integrating green hydrogen into their plants.

By securing a long-term PPA, instead of a CfD, projects (in the UK at least) with costly seabed leases could circumvent what is now a risky, relatively infrequent, and potentially costly CfD auction process, and reach FID faster.

With this competitive advantage, End Users may soon decide to forget about M&A and instead get involved in the very early stages of project development.

For large developers, this new entrant in project development could cause serious problems. As discussed previously, the Round 4 results and competition for seabed has meant many incumbent developers have found themselves without a pipeline in England and Wales. Some of these developers may have already started looking into new markets, but it is likely that after ScotWind, established markets will soon adopt the same auction model as The Crown Estate, which means it’s all about who is willing to pay the most.

If End Users do start to participate in seabed auctions, this could spell the end of the current business models of many developers (which has been to own, develop, construct and operate projects) because if you can’t secure seabed you can’t play the game. If the developers want to retain their development, construction and operations expertise, they may need to consider adopting a similar model to conventional construction management companies, who develop, construct and in some cases maintain and operate projects, but don’t own them.

Their clients in this case would be the End User, or a syndicate of End Users, who want someone to build them a project which gives them the green energy they need to successfully decarbonise their business. They don’t have that expertise, but they know of developers who do.

For the developers who are able to continue to build their pipeline, they should be able to continue as normal. But for many others, this model of working directly for the End User as a service provider will enable them to retain experience, whilst remaining in the game.

Investors

You may assume that the project owner in this case would be the End User. But that doesn’t necessarily have to be the case. As discussed above, the End Users want to remain focused on their core business and exposing themselves to development, construction and operational risk could be distracting and costly. They just want green power.

With incumbent infrastructure investors, pension funds, and other long-term investors keen to invest in green projects and finding the equity market in offshore wind increasingly challenging, many have already started to become active in projects at earlier stages. ScotWind and R4 are two recent examples where traditional investors have signaled they are comfortable with development risk.

Under this new model, with End Users leveraging their energy demand to win leases and circumvent risky subsidy processes prone to delay, there is an opportunity for investors to benefit at the expense of the incumbent developers whose role may be reduced to being a service providers.

Firstly, if the investor partners with an End User from the beginning, using the incumbent developers as a service provider only, they will get better access to the project’s equity.

Secondly, many offshore wind investors are also shareholders in heavy industry End Users. This strategy to partner directly with the End User creates an opportunity for investors to decarbonise and enhance the ESG credentials of their portfolios, whilst also creating new investment opportunties.

Therefore, from both the investor and End User’s perspectives, this arrangement provides both parties with what they want.

Developers may read this and say, “What about us?!”

Well, for many developers the choice may soon be to either persist with a strategy that is not yielding results or accept that in order to remain an important player in the market they may need to focus on their strengths.

This decision comes at a time when the margins in projects are becoming leaner whilst consenting and construction risks in many cases are increasing. This moment could actually be a good time for many to re-strategise.

What to look for

If the industry does start to head in this direction, I think we in the UK may start to see some movement from Q1-2022 as the industry reaches two important milestones.

Firstly, if some developers fail to secure a lease in ScotWind after failing to do so in R4, they will need to think about how they are going to survive in a market where O&G majors and others with pipelines are recruiting at phenomenal rates. The recent news that there were 74 bids made for the 15 areas of the seabed in ScotWind shows that competition is hotter than ever.

Secondly, if some projects find themselves without CfD support in the upcoming 4th Allocation Round, we may see these projects deciding to follow HKZ’s example.

This is an exciting time to be involved in the industry, and we at Everoze will watch with interest to see how the industry responds now that this new player has entered the game.